Analysing the interactions

System evaluation

The first step had been to measure the degree of real success of the dialog system. As the phone calls were intended only for scientific purposes and the speakers proposed fictitious destinations, it is not easy to define what “success” mean. As we will see later, some speakers change their minds during the conversation and accept the destination or travel plans proposed by the system. In those cases, the interaction has not been considered as successful. In other words, an interaction is valid only when it satisfies the speaker’s original goals.

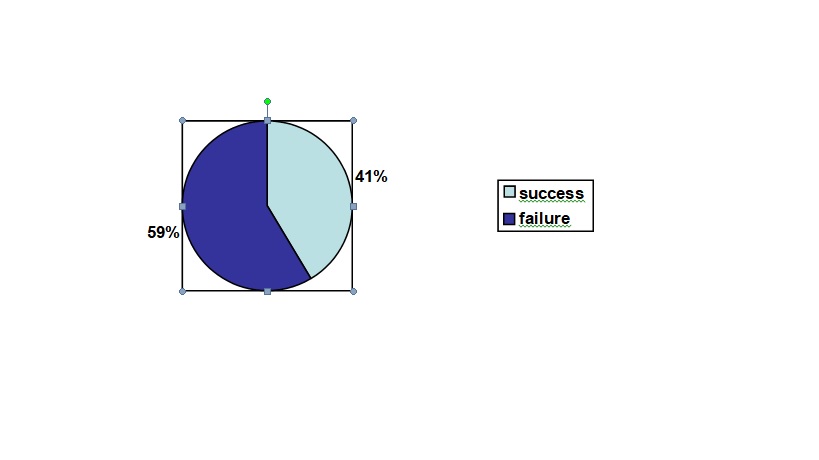

Under these premises, the evaluation results are shown in the Figure 1.

Out of 41 dialogs, only 17 speakers manage to communicate successfully with the system, less than a half of all interactions. Besides the speech recognition problems for a particular speaker, we think that many participants failed to understand the strategy necessary to interact with the machine. On the other hand, the system is not robust and flexible enough to adapt to the human communicative strategy.

Dialog strategies

Instructions

Before proceeding with the actual conversation, the caller listens to the following message:

(1)

*MAC: Puede responder a las preguntas una por una o formular su petición // diga de qué ciudad quiere salir // hable por favor //

[You can answer the questions one by one or formulate your request // From which town do you want to depart? // Please, speak]

With this introduction, the dialog system offers to different communicative strategies:

- The machine plays the dominant role leading the conversation. The speaker only has to reply to the system’s questions.

- The speaker takes the initiative, chooses the information he/she wants to give and in what order. The human plays the dominant role.

The second strategy is the most common in asymmetric interactions between humans, such as the dialogs between salesmen and customers. Nevertheless, in our human- machine recordings, this strategy is not preferred.

System conversational strategy

The strategy used by the machine is extremely simple:

- First, the system demands relevant information by making a question and prompts the user to reply by using the imperative formula “Hable, por favor” (e.g: “¿De qué ciudad quiere salir? Hable, por favor // [From which town do you want to depart? Please, speak]).

- Once the user has answered the question, the system decides whether the answer is intelligible or not. Then, the dialog can progress in two directions.

- If the system has understood the answer, it seeks confirmation by repeating the response. Then, it prompts the user to reply using the same formula as before, e.g. “Quiere salir de Barcelona. Hable, por favor // [You want to leave from Barcelona. Please, speak]”. This is a serious mistake, because the expected answer is just “yes” or “no”. Therefore, for the confirmation a Yes/No question should be used instead. For instance, “¿es correcto?” (is this correct?) or more polite, ¿le he entendido bien? (did I understand you well?).

- If the system is not able to recognise the words, it asks the user to repeat the answer,

e.g. “No le he entendido bien. Repita, por favor // [I did not understand your answer. Please, repeat it.]” Usually, the user repeats the answer and the interaction can proceed.

In short, the system strategy is too limited, because the same formula is used when the machine demands new information (the request) and when it asks for a confirmation. Most of the users are confused by this, as we see later. Surprisingly enough, the dialog progresses better when the system it is not able to understand since the strategy adopted then is better adapted to human interaction.

Human conversational strategies

There are two clearly differentiated approaches:

- Strategy A: the caller behaves as it was a human-to-human conversation, with failure.

- Strategy B: the caller behaves as he/she was talking to a machine. This results in success.

In the following sections, we will describe both approaches in detail.

Strategy A: human-to-human conversation

Here the participant feels as a customer demanding an information service. Accordingly, he or she plays the “customer” role under the implicit principle that the service provider has to satisfy the customer’s requests. This general approach to the interaction with the dialog system produces different failed communicative acts because that system is not able to understand the requests. As a consequence, the communication stagnates, the speaker is frustrated, and the system doesn’t know how to continue.

Analysing the interactions, we have shown three different phases in the dialog:

- Phase 1: parallel strategies

- Phase 2: strategies in the fight to play the dominant roll

- Phase 3: negotiation strategies.

parallel strategies

This first phase is characterised by violation of the strategy proposed by the system. The speaker does not follow the patterns of interaction that the system asks and expects. We will see two examples of these communicative behaviours.

Speaker does not confirm the information: As we drawn 4.2.2., the basic dialog pattern is first to request information from the user, and then either to ask for confirmation of the “understood” information or to demand a repetition. This is the general schema:

(2)

*MAC: ¿de qué ciudad quiere salir? [from which town do you want to depart?]

*MAN: de Madrid. [from Madrid]

*MAC: quiere salir de Madrid, hable por favor. [you want to depart from Madrid, please speak]

The first misunderstanding is caused by the ambiguous “hable por favor” (used for requesting information and demanding confirmation). The machine performs an indirect speech act when asserting “Quiere ir a Madrid”. The illocutionary act in this assertion is a request of confirmation. What system expects from the speaker is just “sí” or “no”. However, the speaker following this strategy never answers yes or no.

It is clear that the pattern “hable por favor” is inefficient in terms of communicative relevance. The system needs that the speaker infers a confirmation of the understood information. Usually in a daily conversation, the interlocutor does not repeat everything that the speaker says. Instead, the speaker uses his or her turn in two ways: a) to contribute new information (example 3); b) to ask another question (examples 4, 5, and 6).

(3)

*MAC: quiere salir de Madrid / y llegar a Santander y viajar en un tren con servicio coche cama // hable por favor //

*WOM: &mm / queremos ir dos adultos y un niño // y llevar el coche //

[*MAC: you want to depart from Madrid/ and arrive to Santander and to travel in a train with sleeping facilities// please speak//

*WOM: &mm / we want to travel two adults and one child/ and to take our own car //]

(4)

*MAC: quiere salir el viernes 7 marzo // hable por favor //

*WOM: a qué hora sale el tren ?

[*MAC: do you want to depart on Friday March 7th // please speak//

*WOM: at what time does the train leave? ]

(5)

*MAC: ¿ en qué tren quiere viajar? hable por favor //

*MAN: qué tipos hay ?

[*MAC: Which train would you like to take? Please, speak//

*MAN: What kind of trains are there?]

(6)

*MAC: en qué tren / quiere viajar ? hable / por favor //

*MAN: &mm qué precios / tienen ?

[*MAC: in which train / would you like to take ? / please, speak//

*MAN: &&mm what are the prices?]

Speaker does not provide the information in the requested order . This is a rather common behaviour in our corpus. Some speakers take advantage of their first turn to send a full request. Then the information is organised according to the speaker’s needs and desires, but it does not respond to the pattern the system is prepared to process.

(7)

*MAN: mire / repito / quiero ir / de Madrid a Huelva / el día dieciséis de marzo / y &eh en un tren / tipo Talgo // que tenga &eh restaurante y [/] y pueda llevar animales //

[*MAN: Look / I repeat it/ I want to go/ from Madrid to Huelva/ on March 16th/ and &eh in a train/ Talgo type// that has &eh restaurant and [/] and that can take animals//

*MAC: quiere salir de Vitoria entre las trece el seis marzo mil ochenta y ocho y llegar a Linares sobre las una y ocho // hable por favor //

[*MAC: you want to depart from Vitoria between thirteen hour on march 6th 1088 and arrive on Linares around one hour and eight // please, speak]

Phase 2: strategies in the fight to play the dominant role

In this intermediate phase, there is an overt conflict between the speaker and the system. Both the machine and the human spend several turns trying to impose their dialog patterns. On one hand, the machine tries to get the information confirmed and only expects a “yes” or “no” answer. On the other hand, the human repeats the same information once and again, looses his/her temper and, denies the system suggestions and uses expressions against the principles of courtesy: “No me importa la hora” [I don’t care the time].

(8)

*MAC: quiere salir sobre las horas doce / y llegar sobre las horas veintitrés // hable por favor //

[*MAC: you want to leave around hours 12 / and arrive around hours 23 // please, speak]

*MAN: quiero salir de La Coruña / el lunes veinticuatro / y llegar a Alicante //

[*MAN: I want to depart from La Coruña / on Monday 24th / and arrive to Alicante]

*MAC: quiere salir sobre las horas doce y llegar sobre las horas veintitrés // hable por favor //

[*MAC: you want to leave around hours 12 and arrive around hours 23 // please, speak]

*MAN: quiero salir de La Coruña / el [/] el lunes veinticuatro marzo / y llegar a Alicante //

[*MAN: I want to depart from La Coruña / on [/] on Monday 24th / and arrive to Alicante]

*MAC: quiere salir sobre las horas doce / y llegar sobre las horas veintitrés // hable por favor //

[*MAC: you want to leave around hours 12 and arrive around hours 23 // please, speak]

*MAN: no me importa la hora // hhh / quiero salir de La Coruña / el lunes veinticuatro / y llegar a Alicante //

[*MAN: I don’t care the time // hhh/ I want to leave from La Coruña / on Monday 24th / and arrive to Alicante //]

This dialog shows the fight for the conversation topic: whilst the machine wants to talk about the time of departure, the user is interested in the departure point, destination and dates. Here the speaker is playing the typical role of a customer, and, as such, he or she thinks expects the system to satisfy his or her demands.

Phase 3: negotiation strategies

At a certain point, the speaker realises that his or her strategy does not work: it takes to much effort for the results. Then, the speaker decides to try other strategies to communicate with the system. The most common have been to yield the dominant role to the machine, and to imitate the system behaviour.

- To yield the role: the speaker gives up and passes the dialog pattern to the system. Then the user just replies the questions made by the machine.

(9)

*MAC: En qué tren quiere viajar ? Hable por favor.

[*MAC: In which train do you want to travel? Please, speak]

*WOM: no quiero el domingo dos de marzo / quiero el viernes siete de marzo //

[WOM: I don’t want the Sunday 2nd of March / I want to go the Friday 7th of March]

MAC: en qué tren / quiere viajar ? hable por favor // [*MAC: in which train /do you want to travel? Please, speak]

*WOM: en un tren con coche cama // hhh // [*WOM: in a train with a sleeping-car // hhh //

- Proposing alternatives: sometimes the user tries to solve the conflict by presenting an alternative to the original request in an attempt to negotiate or, somehow, yield to the machine. This strategy, frequently used by humans to smooth tensions between speakers, it does not help in this dialog system. On the contrary, it adds more difficulties to the linguistic processing, specially, from the pragmatic point of view. Expressions such as “No me importa en qué tren” [I don’t mind in which train] or “Me da igual” [It’s the same to me] urge the system to make a decision for the user and are far beyond the system capabilities. It happens also with phrases such as “otro día” [another day] that require anaphora resolution and complex operations.

*MAN: bueno / pues si no puede ser el lunes / que sea otro día // [*MAN: well / if it can not be on Monday / it can be some other day]

§ The “machine-man” strategy

Another group of participants started to make inferences such as:

- There are misunderstandings because I’m talking to a machine

- How do I communicate with a machine?

- If I want to get success, I must talk like a machine

- How do I communicate with a machine?

As a result, the speaker tries to imitate the way they think the system talks. Here are some examples:

- Changes in the prosody: the caller starts to speak slowly and making artificial pauses between words.

- Telegraphic style: either by using phrases instead of full sentences (10) or by changing the usual “sí” or “no” by expressions extracted from the way robots speak in movies (11):

- Salida nueve diez de la mañana [Departure nine ten in the morning]2

- Negativo / Afirmativo / Correcto [Negative, afirmative, correct]

2 In the usual way the utterance would be: “Salida a las 9 y diez de la mañana”, missing some words.

In short, those speakers behave the same way as if their interlocutor was a person with poor knowledge of the language. Interestingly, they make use of politeness formulae in the form of address, such as the polite “Usted”:

- (12)

*MAN: mire / quiero ir a Huelva [look / I want to go to Huelva]3

In a somehow funny situation, some speakers apologise, assuming their fault, as if they did not want to hurt the machine:

- (13)

*WOM: no / perdón // quiero salir de Córdoba / [no, sorry, I want to go to Cordoba]

Moreover, when they want to end the dialog, some of them say goodbye in the most polite form, as if the information request has been satisfied:

- (14)

*MAC: ¿en qué tren quiere viajar? [which train do you want to take?]

*WOM: bueno / adiós y muchas gracias //

[ well, goodbye and thank you very much]

Strategy B: human-to-machine conversation

The speakers who managed to get the desired information were those who are fully aware that they are talking to a machine with limited understanding. They behave passively in the conversation, following the system pattern. They provide the information in the required order. They confirm with a yes/no when the system asks about. And they do not ask questions. When a misunderstanding arises, they wait for the confirmation turn, reply with a “no” and repeat again the request, talking slowly in order to be correctly understood by the system. This is an example of closing the interaction – note the difference between (14) and (15):

- (15)

*MAC:¿ Puedo hacer algo más por usted? hable por favor.

[Is there anything else I can do for you? Please, speak]

*MAN: no //

3 In Spanish the polite form is the third singular person (mire) instead of the second singular (mira)

In a conversation between people, a usual closing formula would be “no, gracias” [no, thanks]. Interestingly, those speakers never make use of politeness formulae. This is an important difference with respect to the speakers who employ the strategy A, as in (14). While successful communicators are conscious from the beginning that the system will not understand courtesy, the others use politeness for ending the failed communication. The latter do not know that the current dialog systems do not handle courtesy.

Add Comment